Click on IMAGE to enlarge photos. Click on BLUE link to read articles.

AUSTIN FLINT: THE "AMERICAN LAENNEC"

Austin Flint, Sr., M.D., who was recognized as an execptional clinician and teacher, prolific writer, visionary thinker and the forerunner of modern cardiology, was regarded as the "American Laennec" (Dr. Samuel Gross). Austin Flint was a graduate of Havard Medical School where he was a pupil of James Jackson, who was an early advocate of the use of the stethoscope for ausculattion. Dr. Flint was one of the founders of the Buffalo Medical College and Bellevue Hospital Medical College, also taught in Chicago, Louisville and New Orleans before settling in New York in 1861, serving as professor of both the Long Island College Hopsial (now SUNY Downstate Medical College) and and Bellevue Hospital Medical College (now NYU School of Medicine). He was elected president of the New York Academy of Medicine in 1872 and the American Medical Association in 1884. Dr. Flint continued to evolve the art of physical diagnosis and especially percussion and auscultation initiated earlier by Leopold Auenbrugger and Rene Laennec, respectively. His texts on diseases of the heart, respiratory system and manual on percussuoin and auscultation are considered classics. By the time of his death on March 13, 1886, he had a national and internatioal reputation as an esteemed medical professional.

In 1852, George P. Cammann, M.D. desiged a stethoscope that used both ears. This new "binaural" instrument was touted to be the preferred method of auscultation. Also in 1852, Dr. Austin Flint published his prize essay On Variations in Pitch in Percussion and Respiratory Sounds and their Application to Physical Dignosis establishing his expertise in ausculataion of the chest. At first, Dr. Flint was concerned that the transmission of sounds by the binaural stethoscope would be attenuated and that its advantages were not appreciated without considerable practice. In his text on Physical Exploration and Diagnosis of Diseases affecting the Respiratory Organs published in 1856 he stated "In making trial of this instrument, I have found it more difficult to institue comparisons as regards quality and pitch of sound with the ear alone, or the ordinary stethoscope." Ten years later in the second edition of his text publisheed in 1866, 3 years after Dr. Cammann's death, he corrected his opnion stating that "the objection on the score of the alteration of the pitch and quality of sounds I have long since found to be without foundation, and I am sure that this instrument will supplant all wooden stethosopes as soon as it is fully appreciated."

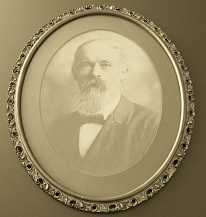

Oil portrait of

Austin Flint, Sr., M.D. shown on the left was a family portrait by the New York painter John L. Harding,

Sr. and is signed and dated 1865 by the artist. Dr. Flint is wearing a

pin of the Freemasons on his vest and Victory of the Cross on his shirt.

The Flint family donated the portrait to the New York Academy of

Medicine in 1900 and was displayed in their Museum Room. The New York

portraitist George

R.

Boynton was

commissioned by

the New York Academy of Medicine to paint a posthumous portrait

of Dr. Flint shown in the center photo. This very portrait was

preseted

to the Academy on January 17, 1901 by Dr. J.E. Janeway on behalf of

himself and 14 other fellows of the Academy who were the donors for the

portrait. This posthumous oil portrait

was signed by Boynton and based on the last known photograph of Dr.

Flint by the New

York portraitist photographer Benjamin J. Falk, as

shown in The Medicine of the Future publication of Dr. Flint's intended

address

to the British Medical Association in 1886, delivered by Dr. Flint's

son, Austin Flint, Jr., on April 24, 1886 after his father's death.

Note that the paisley patterned ascot and stickpin in the painting are

the same as in the photopgraph. The portrait was displayed in the

President's Gallery at the New York Academy of Medicine. John Harding,

George Boynton and

Benjamin Falk were all leading New York artists that were well known

for their portraits

and especially their use of lighting and positioning of the subject.

( Photos courtesy of Alex Peck )

Actually, the idea for a binaural

stethoscope was first introduced in 1829, just ten years after the

publication of Laennec's text illustrated his original instrument. The

idea belonged to Nicholas Comins, who devised a stethoscope that he

described as "a bent tube" that had several hinges, allowing the

physician to not have to assume uncomfortable positions during the

examination. He offered the suggestion of making his instrument

binaural, but there are only sketches of his instrument.

Dr.

C.J.B. Willaims is said to have constructed a binaural stethoscope

using two bent pipes (since rubber was not yet available) attached

to a wood chest piece around 1840. Arthur Leared presented a model

of a "double" stethoscope made of gutta-percha at the Great Exhibition

in London in 1851. The first commertcially available binaural

stethoscope was made by Dr. Nathan B. Marsh of Cincinnati,

patented in 1851. His model was made of india rubber with a long

stem to which a flaring bell made of wood could be attached. However,

it proved cumbersome, very fragile and quickly faded.

The

original Marsh binaural stethoscope, circa 1851. On the left the

stethoscope is in its original wood box. On the right is the assembled

stethoscope.

(photos courtesy of the Marsh family,

Smithsonian museum)

GEORGE CAMMANN: THE BINAURAL STETHOSCOPE

In

1852, Dr. George Cammann of New York produced the first recognized

usable binaural stethoscope. He was working as a physician at the

Northern Dispensary in New York City and had seen Marsh's model. He

also had a model of a soft metal, multiple-tubed stethoscope made by H.

Landouzy in 1841, which was designed for two people to listen at the

same time. And Charles J. B. Williams claims to have made a binaural

stethoscope with lead tubes in 1843. Cammann did not claim to have the

original idea for a binaural stethoscope, only to have developed a

practical instrument that could be used in clinical practice. Interestingly,

he never

patented the stethoscope believing it should be freely available to

physicians. The stethoscope was named Cammann's Stethoscope by the

manufacturer of the original instrument, George Tiemann. Cammann's

model was made with ivory earpieces connected to metal tubes of German

silver that were

held together by a simple hinge joint, and tension was applied by way

of an elastic band. Attached to these were two tubes covered by wound

silk. These converged into a hollow ball designed to amplify the sound,

and attached to the ball was a conical shaped, bell chest piece.

The earliest known original model Cammann binaural

stethoscope made by George Tiemann, circa 1852. This is an exceptionally

rare and important early 1850s initial model Cammann binaural

stethoscope with the front of the yoke delicately hand-engraved Dr.

Cammann's / Stethoscope. Tiemann / N. YORK is stamped on

the reverse side. Note the velvet sleeves covering the

very short tubes. The metal ear tubes are made of German

silver, large and flaring chestpiece was

turned from ebony wood, and the earpieces are ivory. This stethoscope

was obtained from the Intenational Museum of Surgical Science,

Chicago, Il, when it reorganized its science collection and is

the same instrument pictured in American Surgical Instruments, by James M. Edmonson , p. 106, figs. 138

and 139. It is the stethoscope shown in the above detail of Dr.

Cammann's portait.

(Photos courtsey Alex Peck)

Prior

to 1855 George Tiemann marked his medical instruments as Tiemann, after

1855 used the mark G. Tiemann & Co. and later used the mark Tiemann

& Co. The markings on the models shown below help date these

stethoscopes and are consistent with the introduction of the Cammann

stethoscope in 1852.

![]()

![]()

![]()

To the left is an original Cammann stethoscope, circa 1852. The yoke of the hinge joint is hand engraved Dr. Cammann's Stethoscope and the reverse is stamped Tiemann N[ew]. York. This initial model had a large and flaring ebony chestpiece and ivory earpieces. The flexible woven tubes were covered with velvet and were very short as compared to later models. This stethoscope and the one above are the only two hand engraved Cammann stethoscopes known to exist.

The Cammann stethoscope shown in the middle photo dates to 1855. The left side of the yoke of the hinge joint is stamped Dr. Cammann's Stethoscope, but is not hand engraved. The right side is stamped G. Tiemann & Co. Note that the wood bell does not have as large a flare and the velvet covered tubes are a little longer. This is the only example of this Cammann stethoscope known to exist.

On the right is Cammann stethoscope, circa 1860. The left side of the yoke is marked Dr. Cammann's Stethoscope but is not hand engraved. The right side is marked Tiemann & Co. Note that the flexible tubes are longer, not covered in velvet and are attached by gutta percha connectors to the binaural ear tubes. The two parts of the stethoscope could be detached for carrying and reattached for auscultation.

On the left is the only known

carte-de-viste (cdv) albumen print photograph of Dr. Cammann by Matthew

B. Brady & Studio

in New York City, circa 1860, which appears to have been taken at the

same sitting as the salt print photo mentioned above.

Note the Brady backmark on the verso as well as the period ink

signature of G. P. Cammann, M.D. below the backmark. Dr. Cammann

developed the binaural stethoscope in 1852 while

working at the

Northern Dispensary. The Northern Dispensary was instituted in 1827 and

built in 1831 to

provide medical care to the "sick and worthy poor" and was open

continuously from 1831

until 1989. The Dispensary is the only building in New York

City that has two sides on one street (Waverly Place) and one side on

two streets (Christopher and Grove Streets). The three sided building

occupies the triangle formed by those streets. Shown above are the

photos of the Northern Dispensary in 1855 after addition of a third

floor to the 1831 building and in 2006 looking the same as it did in

1855, but now closed and empty for 25 years because the original deed

requires that the building only be used for aiding the sick and worthy

poor. Notice the

young boy pausing on his bike, while trying to decide which fork in the

Waverly Place road to take, which splits into a left and right street

at the tip of the Northern Dispensary triangle. Dr. Cammann was

appointed to the Dispensary in 1832 as an Attending Physician and

worked there for 28 years until he resigned in 1859 and then contiunued

to serve as a Consulting Physician until his death in 1863. Shown

above are photos of pages from the June 7, 1832 and October 7,

1859 minutes of the Proceedings of the Trustees of the Northern

Dispensary appointing Dr. Cammann to the Dispensary and thanking Dr.

Cammann for his faithful service to the Dispensary, respectively. He

was also a member of the St. James Episcopal Church, Fordham and one of

the church's four Royal Bavarian Stained Glass Windows

portraying Saints John and Peter healing of a man by the

Jerusalem Temple's Beautiful Gate, installed when the church was

built on its present site in 1864-65, was in memory of Dr. Cammann for

his humanitarianism. The window dedication reads "In Memory of Geo. P.

Camann M.D. dec. Feb. 14. 1863."

(Nothern Dispensary minutes

courtesy of the New York University Archives, Northern Dispensary

photo by Jefferson Siegel and stained glass window photo courtesy of

St. James Episcopal Church, Fordham).

To

the far left is Cammann stethoscope with elastic band, which was the

original tension mechanism designed by Dr. Cammann, W.F. Ford & Co,

circa 1870. Next is Cammann stethoscope with spring tension mechanism,

circa 1880 and a Cammann stethoscope with Ford's patented wire

spring tension mechanism to hold ear peices together, Hazard,

Harzard & Co, circa 1890. On the far right is a Cammann stethoscope

with screw tension mechanism, Sharp & Smith, circa 1880.

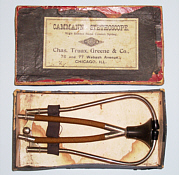

Cammann stethosope in its original tin

case, circa 1870.

The

Cammann stethoscope usually came in a carrying case, although most of

these were lost over time. The cases are more difficult to find than

the actual stethoscopes. Two examples of such cases

are shown below.

Cammann stethoscope, circa 1880, marked Dr. Cammann Stethoscope, Tiemann Co. The tooled leather case is marked Dr. John Hatton (1838-1898) who graduated the Iowa University Medical College in 1870 and practiced in Des Moines.

As the Cammann stethoscope evolved, diffirent materials were used for the metal tubes and bell. Originally metal tubes were made of German silver and chest pieces of ebony wood. Later models of the Cammann stethoscope became simplier in the shape of the bell and metal attachment of the flexible tubes to the metal tubes.

Turn of the century Cammann stethoscope

with small ebony bell marked Weiss, London circa 1901.

As

was the case with Laennec's model, Cammann's was not embraced

completely for quite some time. It was not until Austin Flint (who had

previously spoken against the binaural in 1856) endorsed it in 1866

that it became widely used. During the later half of the 19th century,

well educated physicians used advances in medical technology to aid

their ability to diagnose diseases in their patients. The stethoscope

rapidly became the main symbol of the highly skilled physician.

A

photo dated May 1889 of a physician in his office with a medical text

on his lap, surrounded by medical equipment including a Bauch &

Lomb microscope and Cammann stethoscope on his desk. The use of the

microscope and stethoscope by physicians represents the advances in

technology applied to the practice of medicine in the nineteenth

century.

THE HUSE COLLECTION

The

Harvard Medical School (HMS) was founded in 1782 as the

Massachusettes Medical College in Cambridge. John Warren,

Professor of Anatomy and Surgery, and one of the three original medical

college faculty, was instrumetal in moving the school to Boston.

As there was no hospital in Boston at that time, teaching medical

students was devoid of clinical experience. In 1811, his son, John

Collins Warren, was a leader in establishing the

Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), the third oldest hospital in the

United States. Like most hospitals founded in the 19th

century, MGH was intended to care for the poor. In 1869, a

progressive curriculum was instituted at the school,

new

departments of basic and clinical sciences were established, a

three-year degree program was introduced, and the apprenticeship system

was eliminated. Harvard Medical School became a professional school of

Harvard University, setting the United States standard for the

organization of medical education within a university.

Pictured

above in the middle is the Bulfinch Buiding of MGH, circa 1880, with

its

famous ether dome on top of the buiding. Ether was first used for

anesthesia during surgery at the MGH in 1846. The dome shaped and

glass ceiling of the surgical theater not only enabled surgeons to

operate with natural daylight but also to remain awake while performing

surgery on their sleeping patients as the fumes from ether rose to the

top of the domed amphitheater, as shown in the current photo of the

ether dome on the left. HMS moved off the Cambridge campus

to Boston and was located adjacent to MGH from 1846 through 1883. The

HMS is pictured in the foreground in the photo on right with the

adjacent MGH in the background, circa 1875. In 1886, Reginald H.

Fitz, Visiting Physician at MGH and the Shattuck Professor of

Anatomical Pathology at HMS, published his seminal paper on

"Perforating Inflammation of the Vermiform Appendix; with special

reference to its early diagnosis and treatment". For the first time the

term appendicitis was used to describe the most inflammatory disease of

the right lower quadrant of the abdomen which was caused by

inflammation of the appendix and that treatmant was early surgical

removal of the inflammed appendix.

The

unique medical collection displayed below is from Dr. Charles

Archelaus Huse's medical office circa 1884 in Worcester,

Massachusettes. The collection includes Dr. Huse's Cammann stethoscope,

surgical instrument kit, urethral silver catheters, patient records,

patient receipts, letter from the Dudley & Sheppard instrument

company dated 1877 where Dr. Huse purchased his medical

instruments, medical student ticket to Harvard Medical School

dated 1879-80, and sign from his office in Worcester. Dr.

Huse was born on August 7, 1855 in Worcester, graduated Brown

University in 1878 and Harvard Medical School in 1881. After

graduation from Harvard, he served as the Boston Board of

Health Assistant Port Physician for 14 months stationed at Deer

Island. In the summer of 1882, he moved back to his home town of

Worcester and established his practice of medicine and surgery. He

was a member of the Massachusetts Medical Society and the Worcester

Society for Medical Improvement from 1882-1884. Dr. Huse died

prematurely at age 29 from "peritonitis" after a nine day illness

on July 3, 1884, just two years prior to the publication of the classic

paper by his former Harvard Professor, Dr. Fitz,

identifying the cause of most cases of peritionitis

as the rupture of an inflammed appendix, which required

surgical resection as the definitve treatment. The

Huse antique medical collection represents a truly

unique look at this promising young physician and the practice of

medicine in the late 19th century.

The

middle photo shows Dr. Huse's outside office sign from 136 Austin

Street, Worcester, Massachusettes, circa 1884, along with a ticket

for C. A. Huse to attend Harvard Medical School in 1879-80. On the

left is a potrait cdv photo of Charles A. Huse as a student at Brown

University circa 1878 and on the right is a cabinet photo of him with

his clasmates at Harvard Medical School circa 1881. Huse is

sitting on the steps of HMS in the center of his class

photograph.

Displayed

are Dr. Huse's Cammann stethoscope marked Shepard & Dudley,

N.Y., and surgical instrument kit, obstetrical forcep and urethral

dilators all marked Shepard & Dudley, New York. Also shown is a

letter from the proprietor of Shepard & Dudley, New York,

dated July 14, 1877, to Friend Charles [Huse] asking if he

would like to join their family for a summer vacation. The letter

implies that Charles knew them because he purchased the

medical equipment that he intended to use as a medical

student from their store.

Dr.

Huse kept meticulous records of each of his patients in his

Physician's Day-Book & Journal shown above. Note patient # 7

on page 6 displayed to the left and in a close up of the page

on the right, who Dr. Huse diagnosed as having Dyspepsia on

May 4, 1883. This patient was Miss Winnie Clark whose carte-de-visite

albumin photoghraph, circa 1880, is shown with her wearing a

beautiful Victotian mohair wool hat and ornate gold chain. Hand written

in old stlye dip pen ink on the back of the cdv is

Miss.Winnie.Clark / Worcester Mass, as well as the backmark of

the photographer: Fitton, 345 Main St., Worcester, Mass.

Dr.

Huse's records included individual bills for each patient, a copy of

each bill and a Physician's Hand-Book to keep track of payments. A

routine visit to the doctor cost $1.00 !

THE NAMMACK STORY

Bellevue

Hospital in New York City is the nation's oldest public

hospital. It was founded in 1736 as the Alms House, a six bed

infirmary for the poor, and was located at the site of the current

City Hall in lower Manhattan. In 1794, the Belle Vue farm on

Manhattan's East Side was used to quarantine victims of the yellow

fever epidemic in New York City. In 1811, the Kips Bay farm, just

north of Belle Vue, was purchased by the city for a larger almshouse.

McKim, Mead & White designed the Bellevue Hospital buildings

between 1908 and 1939 that stand today on the land of the Belle Vue and

Kips Bay farms on First Avenue and 27th Street. The Bellevue

Medical College was established in 1861 and the first School of Nursing

in the nation based on Florence Nightingale's philosophy was opened in

1873 at Bellevue. In 1841, the University Medical College was

established as the Medical Department of the University of New York on

First Avenue and 26th Street. The College changed its name to New York

University in 1896. In 1898, Bellevue Medical College and

University Medical College of New York University consolidated as the

University and Bellevue Hospital Medical College, ultimately changing

its name to New York University School of Medicine in

1960. Bellevue Hospital remains today the

nation's premier public hospital and continues its long

tradition of serving as a primary teaching hospital of NYU Medical

Center.

On

the left is a photo of the Unversity College of Medicine (NYU),

1886. On the right is a photo of Bellevue Hospital, 1886.

These

photos are taken from the "University of the City of New York / Medical

Department / Forty-Sixth Annual Announcement of Lectures and Catalogue

/ Session 1886-87 /New York: 1886." In the middle is a view of Bellevue hospital on its 275 birthday in 2011.

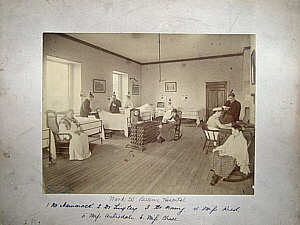

Photo of Women's Ward 20 at Bellevue Hospital in

New York City, circa 1888.

The

photo has a legend identifying the hospital, ward, physicians and

nurses bearing the mark of the Bellevue Hospital Photography

Department, NY City. The enlarged photo on the right shows Dr. Nammack

holding a Cammann stethoscope in his left hand, Dr. Tingley taking

notes, presumaby of Dr. Nammack's ausculatory findings and nurse Ried

with an open chart. Note that Dr. Nammack is also holding his patient's

hand, perhaps to reassure her, as he discusses his observations.

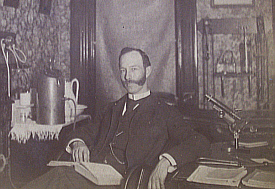

Photo of Dr. Wm. H. Nammack, circa 1900, from the book A

History of Long Island by William S. Pelletreau.

Dr.

William H. Nammack was a 1886 graduate of Bellevue Medical College and

was one of four "successful candidates for appointment in the

Bellevue Hospital ". He served as a House Physician on the 3rd Medical

Division at Bellevue Hospital in 1886-1887. In September of 1887, Dr.

Nammack was appointed the Medical Superintendent of the Insane

Pavillion of Bellevue Hopsital. He remained a member of the outside

hospital medical staff for another nine years. Dr. Nammack was a

physician and surgeon who originally practiced general medicine at 11

Rutgers Street in New York City. In 1892, he established his home

and surgical practice in Far Rockaway. Dr. Nammack was visiting

physician and pathologist at St. Johns's Hospital in Long Island City,

and aslo served as the Coroner of Queens for a number of

years. He was a memeber of the Bellevue Hospital Alumni Society, New

York State and County, Queens County and Nassau County Medical

Associations, and Society for the Relief of the Widows and

Orphans of Medical Men. His son Griswold D. Nammack, grandson

Griswold P.D. Nammack, brother Charles E. Nammack, and nephew Charles

H. Nammack were also all physicians affiliated with Bellevue Hospital.

Dr. Nammack's great grandson Thomas W. Nammack is the Headmaster of The

Montclair Kimberley Academy, Monclair, New Jersey, and provided part of

this history of the Nammack family.

Dr. Witter Kinney Tingley

was also a graduate of Bellevue in 1886 and another of the four

graduates to serve as a House Physician on the 3d Medical

Division in 1887-1888. Dr. Tingley practiced General Medicine in

Norwich, Connecticut and served as President of the Norwich Medical

Association in 1890. He was one of the incorporaters of and Visiting

Physician to Backus Hospital in 1892.

Dr. Robert Alexander

Murray was a graduate of University Medical College (NYU) in 1873 and a

House Physician on the 2d Medical Division from 1874-1875. Dr. Murray

practiced General Medicine and specialized in Disease of Women at 235

West 23d Street , New York City. He served as Attending Physician,

Diseases of Women, at the Northwestern Dispensary, New York City,

from 1876-1883 and Assistant Professor of Obstetrics at University

Medical College (NYU) from 1876-1886. He also served as an Instructor

in Obstetrics, New York Polyclinic from 1887-1888. Dr.

Murray authored various articles on obsterical subjects in medical

journals.

Ms. Ried, Autisdale and Chase were Nurses at Bellevue Hospital.

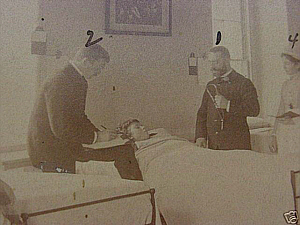

Another

photo of Rounds at Bellevue Hospital from the Bellevue Hospital

Photography Department, circa 1891. Similar to the previous

photo, a physician is using a Cammann Stethoscope to auscultate

the heart of a young patient, while a medical student takes

notes of the physical diagnostic findings and a nurse holds an open

chart.

( Photo courtesy of the NYU School of

Medicine Archives )

THE WHITE COLLECTION

Eclectic medicine was a branch of American medicine which made

use of botanical remedies along with other substances and physical

therapy practices, popular in the latter half of the 19th and first

half of the 20th centuries. "Eclectics" were doctors who practiced with

a philosophy of "alignment with nature," learning from and using

concepts from other schools of medical thought. They opposed the

techniques of bleeding, chemical purging and the use of

mecury compounds common among the "conventional" doctors of that

time.

The Eclectic Medical Institute in Worthington, Ohio graduated its first class in 1833. After the notorious Resurrection Riot in 1839, the school was evicted from Worthington and it settled in Cincinnati during the winter of 1842-3. The Cincinnati school, incorporated as the Eclectic Medical Institute (EMI), continued until the last class graduation in 1939 more than a century later. Over the decades, other Ohio medical schools had been merged into that institution. The American School of Medicine (Eclectic) in Cincinnati operated from 1839 to 1857, when it merged with the Eclectic Medical Institute.

Eclectic Medicine expanded during the 1840s as part of an large, populist anti-regular medical movement in North America. It used many principles of herbal medication but chose to train doctors in physiology and more conventional principles, along with botanical medicine. The American School of Medicine (Eclectic) trained physicians in a dozen or so privately funded medical schools, principally located in the midwestern United States. By the 1850s, several "regular" American doctors, especially from the New York Academy of Medicine, had begun using herbal salves and other preparations.

The movement peaked in the 1880s and 1890s.

The schools were not approved by the Flexner Report (1910), which was

used to decide on accreditation of medical schools. By World War I,

states were adopting curriculum requirements that followed those

articulated by the AMA. Those schools preferred pharmaceutical

medicines to botanical extracts.This effectively forced the Eclectic

Medical Schools to either adopt the new model or fold. Although the

last Eclectic Medical School closed in Cincinnati in 1939, modern

medicine now recognizes "alternative" medicine as a potentially

important adjunct to "traditional" medical therapy

Dr. Harvey A. White was a 1882 graduate of Eclectic

Medical Institute (College) in Cincinnati. After

graduation, Dr. White practiced in

Missouri in 1882, Illinois in 1883, including in Chicago where this

photo was taken in 1904, and White Plains, New York in 1909. He retired

to Tampa, Florida where he died in 1917. Dr. White's Cammann

binaural stethoscope is shown to the right of his photo.

Prior to becoming a doctor, Harvey A. White was a soldier in the

civil war. He enrolled on December 17, 1861 as an artificer in the

newly formed Battery E of the First Illinois Regiment of Light

Artillery commaned by Captain A.C. Waterhouse in the 5th Division under

General William T. Sherman as part of the Army of the

Tennessee commaned by General Ulysses S. Grant. Battery E played a key

part in one of the boodiest battles of the civil war at

Shiloh, Tennessee. In March of 1861, Grant moved his

Union Army up the Tennessee river into west Tennessee around

Shiloh in preparation to attack and seize the Corinth rail junction

that connected the eastern and western Confederate states, hoping to

deal a fatal blow to the Confederacy and end the war quickly. General

Albert S. Johnston also realized the strategic importance of the

Corinth rail junction and poistioned his newly christened Army of the

Mississippi to launch a suprise attack on Grant's forces. As an

artificer, Harvey White could have been in the forward

position with two artillery guns of Battery E confronting the

initial suprise attack by Johnston's Confederate Army on

April 6, 1862. The Confederate forces overran the Union

Army's frontlines and pushed back Grant's forces back to their last

line of defense at the sunken road, later described by a Union soldier

as a "hornets nest" because of the sound made by the constant rain of

bullets fired in that battle. The casualties on the first day of battle

were immense,

including the dealth of the confederate leader, General Johnston.

General Grant was determined to counterattack rather than retreat. On

April 7th with the arrival of General D.C. Buell's Army of the Ohio,

Grant launched an aggressive counterattack defeating

the Confederate forces on the second day of battle. The two

day battle was costly. More Americans fell at Shiloh than the

total casualties in all of the previous wars

fought by the United States. According to the official records 23,746

men were killed, wounded or missing and both sides now realized that

this would be a long and bloody war, just as Dr. Robinson had predicted

in his letter to his father written the previous year on April 28,

1861 (see Dr. Robinson's story in the previous page).

Shown above in the top figure is the 1890 Prang and

Thulstrupt print of the Battle of Shiloh of Union forces last line of

defense at Hornet's Nest at 9am on April 6, 1862. The photo on the left

is the forward position of the two guns of

Battery E, First Illinois Light Artillery with a marker of the

site of the initial battle of Shiloh at 6am on April 6th. The

plaque on the marker

reads "Waterhouses's Battery, 'E' commaded by 1. Captain Waterhouse,

Wounded. 2. Lieut. A.E. Abbott, Wounded. 3. Lieut. John A. Fitch. Two

guns of this battery were advanced about 300 yards but soon fell back

to this position where the whole battery went into action. This ground

was held from 7:00 A.M. to 9:30 A.M., when the battery lost two

guns and moved back about 100 yards. Its loss in the battle was 1 man

killed; 3 officers wounded and 14 men wounded; total, 18." Harvey White

was given a medical discharge by order of General U.S. Grant at

Monterey, Tennessee on June 10, 1862 for a neck injury suffered in the

battle of Shiloh. The carnage that Harvey White witnessed at

Shiloh may have ultimately lead him to become a doctor.

Several physicians came up with their own ideas for

stethoscopes using materials that were commonly found in a physician's

office. For example, in 1884, E. T. Aydon Smith described a stethoscope

he invented: "..the chest-piece of which is formed by a pair of

ear-specula, the tubes are Jaques' India-rubbercatheters, and the

ear-pieces those of an otoscope."He designed his instrument to be used

as a simple binaural, a differential stethoscope (by using one of the

ear-pieces and chest-pieces for each ear), a tourniquet (by wrapping

the rubber around the arm) and, also as a urinary catheter for both

males and females. Quite a diverse instrument!

Another modification was Dr. D.M. Cammann's modified instrument

(Dr.

George Cammann's son), which incorporated a chest piece with a rubber

ball, which was used as a suction cup to apply it to the chest. This

would leave the hands free to percuss to chest. It was found to be of

little value to the untrained ear.

|

READ DR. CAMMANN'S SON'S ADDRESS REGARDING HIS MODIFICATION OF HIS FATHER'S STETHOSCOPE |

New

improvements to the stethoscope focused on the tension mechanism to

hold the ear-pieces to the head of the physician. There was a design of

a spring-tension mechanism which had a screw that could be turned to

open or close the ear-pieces. The first of these new models was

KNIGHT'S model, which had a characteristic design on the poles that

attached to the ear-tubes. The Charles Truax catalog of 1890 states that

"Knight's stethoscope does not differ materially from the pattern of

Cammann. The principal change is in the form of the spring, which in

this case is spiral, acting on two levers in the form of a toggle

joint."

The screw mechanism became a great success

and would be included in the models that followed for many years.

On the left

is a late 1860s Cammann's binaural stethoscope with the

additon of an adjustable tension mechanism to the ear tubes that was

described Dr. Frederick

Irving Knight of Harvard. The instrument is known as

Knight's binaural stethoscope. However, the credit for

this design belongs to Moses G. Farmer as Knight referenced

in his article in the Boston Medical Surgical Journal in 1869. The

metal work is German silver, the flexible tubes covering is woven silk,

the bell and junction are ebony, all characteristics of an early

Knight's double stethoscope by the original maker Codman &

Shurtleff, Boston. To the right is a Knight's

Stethoscope with two bells and a Flint Pleximeter and Percussion Hammer

that is shown with its original wood carrying box, Codman &

Shurtleff, Boston, circa 1880. On the left the instruments are shown

out of the box and on the right placed inside the box. The bells were

interchangeable in that each could be screwed on and off the body of

the stethoscope depending on the choice of the physician.

The larger bell was used for auscultation of the lungs and smaller bell

used to localize heart sounds. Note the metal work is now plated

silver. (Photo on left

courtsey of Alex Peck)

Bartlett's Stethoscope shown on the

left was a heavier version of the Knight model, circa 1880.

Bell's Stethoscope, circa 1875, has an all metal chest piece with

rubber rim in this adaptation of the Knight model.

The Cammann

stethoscope on the right has an unusual horn bell, brass ear

tubes and ivory ear tips and is marked H.G. Kern, Philadelphia,

circa 1860.

There

were many different modifications to Cammann's original instrument.

Scott Alison came up with a 'Differential Stethoscope' that consisted

of two independent chest pieces, and was designed to allow the listener

to compare the sounds of two areas of the chest. This instrument was

also found to be impractical because it muffled certain sounds. Most

references list this piece as circa 1885, but it was actually first

illustrated in the John Weiss & Son catalog in 1863.

Alison's

Differential Stethoscope is displayed on the left, circa 1850. The

close up shows the ebony bell chest pieces. It is signed "Ferguson."

Mr. David Fergusson of Giltspur Street, London was the well known

instrument maker for the Bartholomew's Hospital in London and

introduced many of the new instruments that were used in the hospital.

On the far right is an example of a modern

differential stethoscope with metal diaphragm chest pieces,

circa 2000 and next to it is a differential Stethoscope with

plastic bell chest pieces, circa 1930.

In

1885, Charles Denison came out with an entirely new model, based on

Bartlett's. His was based on the idea of funneling sound to the ears,

much like the monaurals. His earpieces were made of hard rubber which

led into woven tubes and a large chest piece. It came with three

interchangeable chest pieces for hearing different types of sounds. The

tension between the earpieces was accomplished by a clever screw

mechanism.Denison's model was widely accepted. So widely,

that many makers began marketing inferior pieces of the "Denison

Stethoscope." Denison became outraged at the poor quality of

stethoscope being manufactured with his name. He delivered a powerful

speech in which he stated precisely how his stethoscope was to be made,

condemned the makers of poor instruments, and praised one American

company for their quality craftsmanship.

Denison's Stethoscope, circa 1885.

Left example with multiple size bells, courtesy

of the Mutter Museum. Right

examples are in this collection, shown without and with large bell. The

stethoscope was used withhout the bell for auscultation of

children.

Davis modification of the Cammann Stethoscope which incorporated a wire metal tension spring between the metal ear tubes. In this early model, the wood chest bell was attached to the ear piece by a flexible tube which inserted into the wooden ball connecting the ear piece, circa 1880. On the right is a later model Davis stethoscope with simple bell and metal tension mechanism between ear pieces, circa 1890 .

On the left is a Matthews stethoscope with

detachable chest piece and ear tubes for easy portability, circa 1882.

Shown on the right is a very

unusal folding stethoscope with ivory ear pieces and a unique bell that

is a smaller version of the original Cammann bell with a insertable

plug designed after the William's plug, circa 1890. This two piece bell

is made of wood and allowed the auscultator to change the size of the

bell by inserting or removing the plug.

Convenience

came in several ways. Longer tubes added more flexibility, but other

methods were used as well. Around 1880, Lynch's stethoscope was

marketed, which folded onto itself and thus greatly reduced it's

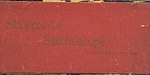

length. Sheppard's model (1890), by contrast, folded the earpieces

together reducing the width of the instrument.

Lynch's folding stethoscope, circa 1880. This piece folds top to bottom as shown on the right. Sheppard's folding stethoscope in its original box shown on the right. This piece folds in half. On the left is the top of the cardboard box which is marked "Sheppard's Stethoscope / patented July 7th, 1890."

The

next landmark improvement was the invention of the 'Ford's Bell' chest

piece in 1885. This simple model was made of steel with either

gutta-percha, ebony, or even ivory at the base. It funneled sound into

two tubes, usually made of rubber, which led to the earpieces.

Three

examples of early Ford's bell stethoscopes with a simple metal band

tension mechanism holding the ear tubes together. On the left

the Ford's bell is made of ebony, circa 1890. In the middle the Ford's

bell chest piece is made of ivory with,circa 1895. On the right the

Ford's bell is made of metal, circa 1895.

Three examples of binaural stethoscopes

with interesting tension mechanisms to hold ear tubes together.

On

the left is a Down Brothers stethoscope with finger rest, interesting

screw spring tension mechanism, ivory ear tips and Ford bell made of

ivory, circa 1900. The ivory bell unscrews to creat a smaller bell for

the examination of children. In the middle is a binaural stethoscope

marked Gallante, circa 1890. The wood chest piece and ear tips are

typical of French binaurals of this period. Note the spring tension

mecahnism between the ear pieces. The right photo shows a Holborn

stethoscope with a slender, wood bell typically used for

children, Herschel's locking mechanism with lever and ivory ear

tips, circa 1900.

The left three examples areDown Brothers

stethoscopes with Ford's bells made from differnet materials.

On

the left the stethoscope has a finger rest and Ford bell made of

aluminum, circa 1920. In the middle is a folding stethoscope with the

mark of the "British Army" with ivory Ford bell and wood ear

pieces, circa 1910. On the right is a folding stethoscope with an

anti-chill, rubber cushioned Ford bell, circa 1910.

Binaural stethoscopes with flexible rubber

tubes to connect the ear pieces to the chest piece, circa 1880.

The

example on the left is Chinese and has ivory ear pieces and a

reversible ivory chest piece. Each end of the reversible chest piece

was a different size and shape, presumably to examine different parts

of the body. The middle ivory example is Japanese. The one on the right

has a gutta percha chest piece.

Examples of two American Phonendoscopes made by G.Pilling & Co. On the left the phonendoscope is in its original velvet lined, wood box, circa 1909. The photo in the middle is another phonendoscope in its original metal case with the chest piece in the case and its extension screwed onto the top for carrying. To the right the stethoscope is put together for auscultation with the ear pieces made of gutta-percha attached by flexible tubes with metal ends to the chest piece and the extension tube screwed into the diaphragm of the chest piece.

Three examples of phonendoscopes made in Europe. On the left is a model with an adjustable valve to vary the intensity of sound made by Osker Skaller A.G. of Berlin. In the middle is a German model with gutta percha ear pieces and on the right a similar French model with glass ear pieces, circa 1900. All the phonendoscopes are displayed in their original, velvet lined, leather covered,carrying cases.

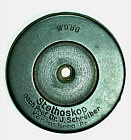

Schreiber's Stetheskop made of metal,

circa 1900.

As

shown from left to right, it could be set up as a monaural or by

sliding the chestpiece down the stem to expose the shaft, a

phonendoscope chestpiece could be attached to the stem. A close up of

the phonendoscope chestpiece is shown on the far right.

Wincarnis

stethoscope, circa 1890. On the right the stethoscope chest piece is

shown in its original case. On the left the flexible tubes with ivory

ear pieces and the chest piece taken apart are displayed. Note the

plastic diaphragm against which either of the two wooden disks would

rest

Marsh's Stethoscope, or

Marsh's Stethophone, is a very interesting invention. It comes with a

small dial on the back which has a pointer and the letters 'L,' 'S,'

and 'W' engraved on it. These stood for 'Loud,' 'Soft,' and 'Weak,'

respectively. The examiner would dial in the type of sound he was

listening to in order to be able to hear it better.

Marsh's Stethophone, circa 1896

This is one of two examples known. The other is in the collection of

the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

Magniphone Stethoscope, circa 1900.

The piece below is very interesting in that it combines the binaural ear piece of a stethoscope with a very long tube and wide bell charcteristic of a hearing aid or conversation tube. In fact, this piece is neither a stethoscope or hearing aid, but rather a "re-educative binaural tube to enable the patient to read or speak to himself and thus stimulate the dormant auditory centre by natural means of the voice" in order to treat middle ear deafness (Mayer&Phelps, circa 1931).

We are always interested in acquiring new items for the collection. If you have any items for sale or question please do not hesitate to contact us.